Passivhaus for Scotland

Passivhaus is making its mark in the wake of COP26. But are we doing enough?

By Barry Dalgleish

In May 2022, Alex Rowley MSP introduced the Proposed Domestic Building Environmental Standards (Scotland) Bill into the Scottish parliament. The aim is to set a standard that all new-build homes comply with the Passivhaus standard ‘or a Scottish equivalent in order to improve energy efficiency and thermal performance.’ In December 2022, the Scottish Government gave the green light for the bill to pass through Parliament. Patrick Harvie MSP, Minister for Zero Carbon Buildings, Active Travel and Tenants' Rights, confirmed that the bill would be fast tracked into law. Harvie stated that:

“…the Scottish Government will be giving effect to Mr Rowley’s proposed Domestic Building Environmental Standards (Scotland) Bill.

“…we have set out our aim to make subordinate legislation within two years, to introduce new minimum environmental design standards for all new-build housing to meet a Scottish equivalent to the Passivhaus standard.”

This is a move that should be welcomed with open arms. But the caveat here is that the standard applies only to new build homes. What is needed is a plan to retrofit existing housing stock. In response to the Bill, the Law Society of Scotland asks the question, Passivhaus – the golden ticket to net zero? The gist is that following the legacy of COP26 in the country, it appears that Passivhaus is now higher in the ‘net zero’ list of priority initiatives than its ever been, with energy conservation in the past playing second fiddle to other initiatives. The article does note that retrofitting existing buildings won’t meet the stringent conditions of new build, where the standard is very much part of the build. Nevertheless, given the poor thermal performance of much of our existing stock, upgrading should be first priority. The Passivhaus Trust outlines how this can be done, whilst conceding that it would be a ‘colossal challenge’:

It’s also a complex undertaking. Every home is different which means some efficiency measures that work on one project may not be appropriate for another. Get it wrong and you could end up with damp and rot. Getting the right contractor with the right skills and experience is also a worry for most homeowners.

Passivhaus has a retrofit standard called the EnerPHit Retrofit Plan. This calls for a measured approach towards upgrading existing buildings. This is something that would require a coordinated approach from all relevant parties from Government to local authorities and contractors.

The following diagram is a graphic illustration of the space heating demand of typical UK housing types:

The following video outlines the process:

The report, Passivhaus retrofit in the UK, covers the main points. It cites four clear facts concerning UK building stock, that underpin the imperative of adopting the standard:

It currently produces 23% of our carbon emissions with 16% alone coming from our homes

It is not fit for purpose with 3.3 million households living in fuel poverty

It consists of millions of poor-quality buildings, which have a detrimental impact on our health

It is not optimised for a decarbonised grid

It cites a report from Committee on Climate Change that has noted the poor response to home insulation. If a retrofit program is to be effective it must also include non domestic buildings. The benefits are clear. Not only does it have an impact on carbon emissions, but it tackles fuel poverty, reduces energy bill costs and alleviates poor health related to many of the problems from cold homes such as dampness and mould. And conversely, homes that are too hot in summer, which will become more prominent in the future as global temperatures rise.

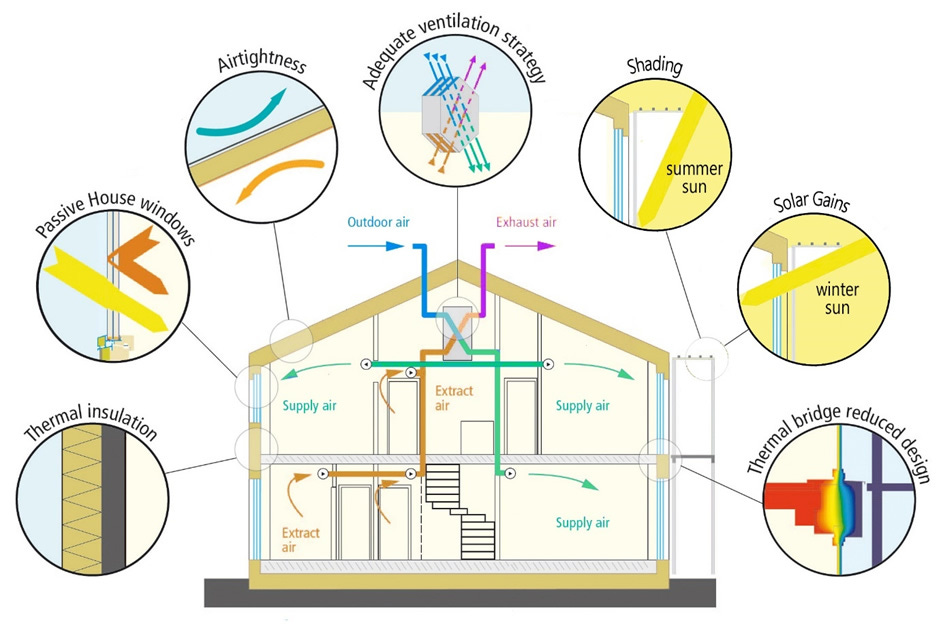

Another health concern is poor indoor air quality. This can stem from construction materials, which can be a source of VOCs. Other sources from cooking, household and personal care products can cause internal pollution. Pollutants can also be biological. The recent pandemic can owe its spread to poor ventilation. The report makes clear that:

Poor indoor air quality can lead to respiratory and other health concerns. Understanding and controlling building ventilation can improve the quality of the air we breathe and reduce the spread of respiratory viral diseases, including the virus that causes COVID-19.

The report acknowledges though that it will take time and money to bring buildings up to reasonable standard:

Retrofit can often be difficult and expensive. Existing buildings come in a wide range of shapes, sizes and ages, many of which are difficult to bring up to exemplar standards of energy efficiency. So, in determining what depth of retrofit is required, we must be pragmatic about what can be achieved and balance that against what is necessary.

With so much attention on renewables, there is an assumption that somehow these will provide a limitless source of energy and that in a world full of windmills and solar panels, everything will come up roses. There are limitations here as well. Also there’s a finite load that the national grid can carry. The report spells it out:

It is estimated that the peak thermal load currently demanded by our homes and delivered by gas is 170GW. The current electric grid capacity is around 100GW. The National Grid’s 2021 Steady Progression scenario projects a requirement to increase total grid capacity to 240GW by 2050 to meet the needs of all sectors - and this won’t even get us to zero carbon. To reach net zero, the more ambitious Consumer Transformation scenario increase is even more dramatic, requiring an increase in peak capacity to 374GW by 2050, almost 4 times the current level!

In short, in order to accommodate future demands from just about every energy consuming source you could possibly think of, overall demand needs to be reduced. Heat pumps are the widely recommended alternative to current gas systems. But the report indicates that these would only be effective in energy efficient buildings, also noting that electricity is four times more expensive than gas. If not implemented properly, heat pumps could end up being counter productive. But with a proper retrofit, space heating demand could be reduced by 80%.

The report refers to a report from the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), Built for the environment. This report outlines in greater depth the wider impacts of the built environment that includes climate, biodiversity and ecosystem impacts. Globally, 38% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are linked to buildings and construction. From a biodiversity perspective, it’s estimated that natural capital per person declined by around 40% (natural capital can be defined as the world's stock of natural resources, which includes geology, soils, air, water and all living organisms).

Under the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) as defined in the Paris Agreement, the report notes that:

Although almost all countries who signed up to the Paris Agreement have submitted their first NDC, many are yet to submit their second. The built environment lacks specific mitigation policies despite its important potential for reducing global carbon emissions. Just over two-thirds of NDCs mention buildings, but a significantly smaller proportion mention energy efficiency or building codes.

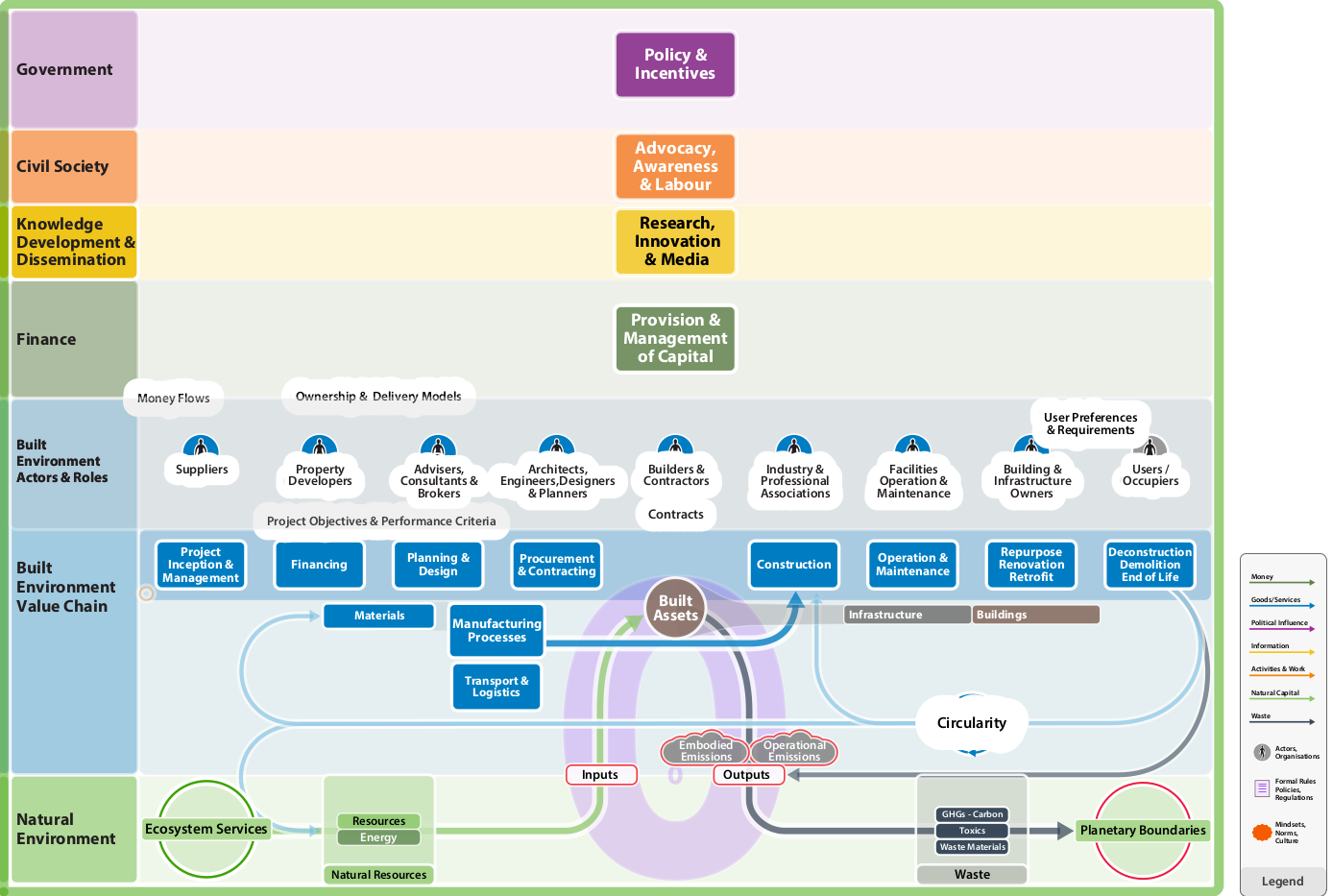

Dealing with these issues on a wide scale will be a complex challenge that will require a holistic multi-disciplinary approach that covers related sectors and actors within the built environment. Put simply:

We should consider all aspects of the built environment, such as strategic planning, extensive urban greening, food production effectiveness, land restoration and habitat conservation.

This approach has been developed further through the Race to Zero Built Environment System Map. Generated by the UN, it’s an interactive space that anyone can access.

A systems approach is emphasised throughout the report. The need for additional research on the impact of climate change is also noted. The necessary push must happen at all governance levels from local to national. Participation is a vital component here, involving local groups and communities:

Participatory planning and user-led design processes make it possible to design schemes that meet carbon targets more effectively because they are site-specific and sensitive to diverse social needs. Built environment projects that draw on participation from local groups and communities can nurture social, ecological, and human development as well as meeting decarbonisation goals.

Design and repair considerations will be important. In addition to retrofitting, repurposing existing buildings not in use would reduce demand for new build and could potentially cut emissions in the building and infrastructure sector by around 12%. This would involve restoring, adapting, or repairing existing buildings. New build could be designed in a manner that would allow future modifications to the original specification. Circular construction in other words, that would fit into the circular economy concept. One example on the island of Eday, used a ‘digital twin’, which is ‘a virtual representation that serves as the real-time digital counterpart of a physical object or process’:

Digital twins can be used to minimise waste or excess wind generation, improve building efficiency, and create a Zero Energy Community. On the Orkney island of Eday, digital twins and community surveys were used to determine ways to reduce the community’s reliance on grid imports using retrofit, integrated renewable generation, and sensor controls. It was found that a Community Net-Zero status could be won with a combination of retrofit measures achieving energy savings of 76% and eliminating fossil fuel consumption on the island by relying on the existing wind turbines and a community battery. The project would pay for itself in 5.6 years, or even sooner if homes were found to be eligible for retrofit funding under schemes such as the Energy Company Obligation (ECO) scheme.

Excess construction materials can be reduced and the use of bio construction materials will all contribute to greater sustainability. And there’s a positive recognition within the built environment sector that change is needed. There’s a commitment to up-skill and educate. This is reflected in various initiatives such as Architects Declare, Built Environment Declares, and the Architects Climate Action Network. It goes without saying that rolling out such a process would create jobs and would be a long term investment for both the construction industry and owners. Another approach is to move to a modular design. The report sums up the advantages here:

Modular construction has several benefits including less material waste and better working conditions. Factory-controlled conditions can reduce costs through a better quality of build, better finishes, and fewer defects, meaning certainty that you are getting what you pay for and less on-site labour. Modular projects can be up to twice as fast as traditional construction projects. By choosing offsite modular construction, traditional processes like site foundation work can occur at the same time as the modular units are being made.

In Glasgow, the West of Scotland Housing Association is building 36 new Passivhaus homes in Dalmarnock, with another project taking shape in Nitshill. Glasgow City Council has produced a presentation from the 2018 UK Passivhaus Conference, linking into Glasgow’s Climate Change Strategy. There is also a retrofit project taking place in in Govanhill, involving a pre-1919 red sandstone tenement in 107 Niddrie Road.

The building is owned by the Southside Housing Association (SHA), and the project was carried out in collaboration with the Scottish Government and GCC, to the EnerPHit standard. The architect (John Gilbert) sums it up:

We have upgraded the building fabric to minimise the heating demand by ensuring the whole envelope is wrapped in high levels of insulation, minimising thermal bridging and ensuring there is a continuous airtightness line, including continuity at all key junctions (eg. at eaves level, windows etc.) General building repairs have been carried out including a repair / restoration of the sandstone street facade.

Four flats are heated by individual air source heat pumps (ASHP) which take heat from the external air and uses it to provide hot water for radiators and domestic hot water. The four upper flats are heated by new efficient combi gas boilers.

All eight flats have their own mechanical ventilation heat recovery unit (MVHR) installed above the ceiling in the bathrooms. These extract moist / stale air from kitchens and bathrooms while bringing in fresh air from the outside. The heat exchanger transfers the heat from the stale air to the fresh to minimise heat loss which reduces the heating demand.

The upper six flats have wastewater heat recovery units installed to the bath / shower so heat can be recirculated back into the hot water system to reduce the water heating demand.

The net result is that heating demand has been reduced by 90%. If this was reproduced universally, the impact on carbon emissions would be dramatic.

These initiatives are noted briefly in GCC’s Glasgow’s Climate Plan report (p43). It notes:

Glasgow City Council’s Housing and Regeneration Services, together with partners from across housing associations, the private sector, and universities, are delivering Passivhaus developments around Glasgow.

In 2021, the Cooperative Loco Home Retrofit CIC was founded. It’s a ‘Glasgow-based co-operative of householders, contractors and advisers focused on promoting energy efficiency within our homes, tackling the climate crisis and keeping energy bills affordable.’ It appears to be making its presence felt in the City As a communtiy orinetated company, it’s keen to expand its services and will be interesting to see where it’s headed.

GCC has also published Glasgow’s Adaptation Action Plan 2022-2030. It makes reference to the City Development Plan that will:

Require developers to include adaptation onto development projects, undertake sympathetic retrofitting measures for older buildings, and other measures such as incorporating green roofs, green walls and/or rainwater collectors on buildings where appropriate.

There’s no doubt that this is an area that should be a key focus of environmental groups. Friends of the Earth Scotland and its sibling south of the border doesn’t have a specific policy here. But FOE Europe published a report in June 2022, Bringing climate action to our doorstep: delivering Fossil Free Homes by 2030, with a clear message:

swift and substantial action to kickstart subsidised renovation and renewable programmes across Europe is an act of climate justice. We must provide healthy, decent housing powered by renewable energy this decade.

This then should be a starting point for a wider campaign to improve the built environment.

This article was updated on 2 January 2023 to include information on Loco Home Retrofit (thanks Liz!).